The Hmong (pronounced: “muhng”) are an indigenous group in East and Southeast Asia. Historical records indicate that they originated in Southern China and spread through the area that is now Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos. They have a complex and fraught history of persecution, migration, and conscription by Western powers to participate in wars in Southeast Asia. Following the North Vietnamese invasion of Laos in the 1960’s the US trained Hmong men to serve as a Secret Army. After the communist victory, many Hmong were forced to leave their country and some repatriated in the United States with the majority of Hmong communities in California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Some Hmong remain in Laos and in the northern regions of Thailand where they are part of the hill tribes as well as northern Vietnam and eastern Myanmar. They are a stateless group, lacking any national identity. The Hmong were an oral culture and did not have a written language until it was created by westerners in the 1950’s.

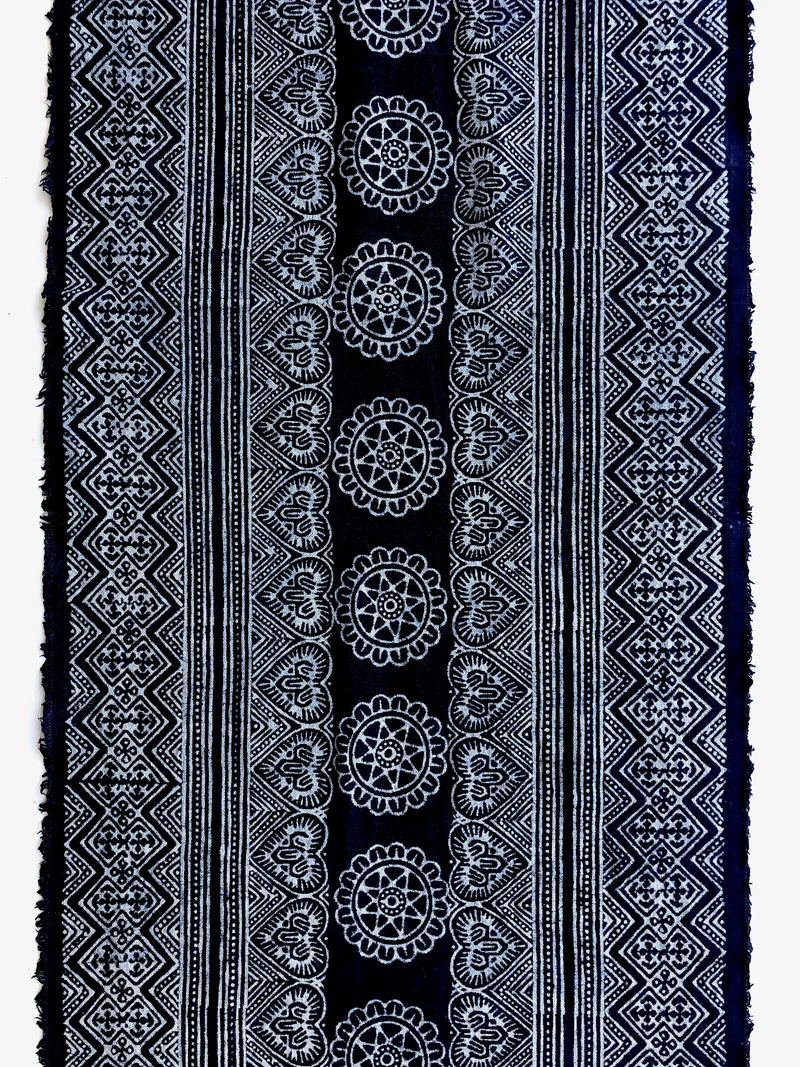

During my travels in Southeast Asia, I was particularly impressed by the wonderful clothing and textiles of the Hmong. Women wear beautifully colored dresses of many layers, adorned with embroidery and metal amulets or jewels. Beautiful blue and white batik fabrics could be found in markets and, behind the scenes, I observed Hmong women painstakingly painting on fabric with wax and wooden tools. I began to recognize two major subgroups in Vietnam, the White and Black Hmong, by the different styles of female dress. Other primary groups include the Green Hmong and Flower Hmong. These subgroups reflect the cultural migrations of different groups and can be identified by differences in dialect as well as dress, for those who speak Hmong.

Hmong textile art includes hand-spun hemp cloth, basketry, batik dying, and a form of embroidery known as “flower cloth” (Paj Ntaub). In the west, the most widely recognized folk art is a form of embroidery derived from Paj Ntaub known as story cloth. Cloth is embellished with a variety of embroidery techniques, applique, and batik. Historically, the cloths employed stylized, geometric motifs and are often used to decorate clothing. Interestingly, more recently cloths began to depict narratives, often focusing on forced migration, military occupation, and refugee life, along with folktales and depiction of traditional life and culture. It is thought that the modern story cloths reflect to some degree western intervention in refugee camps (many cloths include English language) and were created primarily for export and commercial purposes. At the same time, they provide links to Hmong history and culture for members living in the diaspora. Attentive readers will observe that the use of textiles to convey historical narratives in groups with oral traditions is also observed in the Patua scrolls of northern India featured in a previous blog!

The richness and creativity of Hmong women (yes, it is women who produce the majority of textiles) is remarkable and a testament to the power of artistic traditions. Contemporary websites and exhibitions of Hmong textile art have noted the ways in which this textile tradition has served to reinforce a sense of community, particularly in refugee communities (see, e.g. https://www.crosstimbersfinearts.org/ragin-cajun-arti-gras-2020). To their credit many Hmong continue this tradition of artisanship, although its survival in assimilated communities may be in jeopardy, particularly as young women pursue more lucrative occupations available to them in the West.

While we may balk at the notion of crafts being specifically created for western markets, this is also an example of good business skills, particularly in refugee communities. Of greater concern is the wholesale appropriation of native crafts by western companies without acknowledgment or compensation. A group in Luang Prabang, Laos, has sought to address the appropriation of designs of the Oma, a small rural tribe, by the company Max Mara. Despite threats of legal action and social media campaigns, no recourse has been obtained

(https://laotiantimes.com/2023/10/18/new-exhibition-on-cultural-misappropriation-opens-at-the-traditional-arts-and-ethnology-centre-in-luang-prabang/). It is further noted:

There is currently no international legal framework obliging companies to seek consent from or to pay compensation to communities for their shared cultural knowledge. This can be highly damaging to the cultural sustainability of these communities as well as a risk to the economies of countries like Laos, with large handicraft sectors that are crucial to rural supplementary income generation, particularly for women.

Of course the skills of artists should be recognized and disseminated but they should be appropriately compensated as well.

_edited.png)

Comentarios